Most people don’t consider archaeology when they think about forestry.

Matt Ritchie, from Forestry and Land Scotland in this guest post talks about the importance of archaeology and its central role in stewardship of Scotland’s national forests and land on the example of Cracknie Soutterain.

Forestry and Land Scotland

As a Scottish Government agency responsible for managing Scotland’s national forests and land, we manage many interesting and important archaeological sites across Scotland and are finding and protecting more each year. This can involve creating detailed records of significant sites, developing conservation plans to ensure that heritage and visitors are looked after, and investigating and presenting the stories they can tell.

A tight squeeze

The remote Iron Age souterrain (or cellar) of Cracknie in Borgie Forest in Sutherland was built over 2000 years ago. Measuring over 13m in length, and about 1m in height, the narrow curving passage slopes downwards to reach a small chamber at the end. The entrance is marked by a narrow hole in the ground – no stairway or above ground structure survives. The walls are carefully built without mortar and it is roofed with large lintel stones overlapping each other.

Cracknie Souterrain is one of the best-preserved Iron Age souterrains in Scotland, and is one of the most important scheduled monuments on Scotland’s national forests and land.

Souterrains are still an enigma. They were usually built below a large timber roundhouse, and may have been used as cold cellars to store food such as cheese and butter, or as a secure place to house slaves or hostages. They may even have been used for religious and spiritual activities.

Surveying underground

The souterrain was recently the subject of an archaeological measured survey by AOC Archaeology. The survey used modern laser scanning techniques to create a stone-by-stone architectural record. The survey results illustrate the well-preserved walls and roof lintels, and supported the excavation of the entrance passage, opening the narrow hole to enable safe access.

Thie time-lapse video below shows the archaeologists first excavating the narrow entrance and removing a collapsed lintel stone. It then shows the conservation stonemason rebuilding the side walls of the now consolidated access way. The archaeological excavation did not uncover any steps down into the souterrain, so it’s likely that the current access is down through the collapsed roof into the passage, and that the original entrance remains buried.

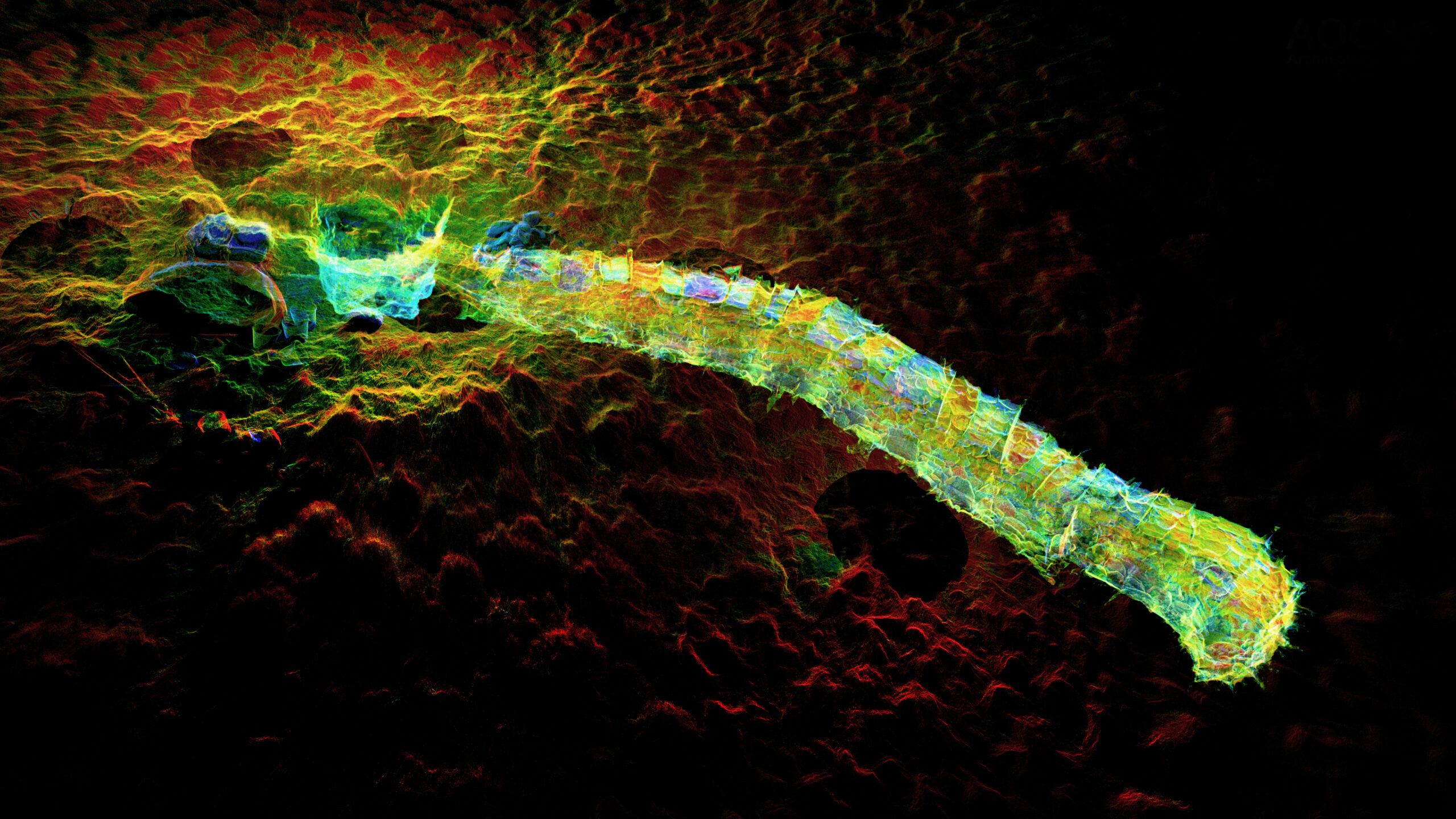

This video shows the 3D point cloud generated by the laser scan survey. You can see where the archaeologists were excavating at the entrance. At the time of the laser scan, they had lowered the ground surface but had not yet opened up the narrow neck of the passageway. The subterranean nature of the space is easy to appreciate. The white wave is a clipping plane, effectively ‘slicing’ through the 3D model – first as a vertical plane from the side, and then as a horizontal plane from above. The dark circles on the ground are scanner positions – the data was collected by scanning above and below ground, and then stitching the two datasets together.

The colours indicate the laser reflectance intensity of every stone in the walls. To understand the image, look for the entrance excavation (on the left hand side) and imagine crawling through the narrow neck of the passage way before crouching low under the lintel stones (visible in the roof of the 3D structure) to reach the chamber at the end, the deepest part of the structure.