The Dogger Bank Wind Farm phases A and B in Yorkshire’s East Riding provided a fantastic opportunity to explore the archaeology of a landscape. Numerous archaeological investigations were carried out alongside works for the onshore infrastructure of the project, revealing finds and features dating to the Prehistoric, Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods.

This is a joint venture partnership between SSE Renewables, Equinor and Vårgrønn. Collectively, the three phases of the wind farm will form the world’s largest offshore wind farm. It is being built 80 miles off the Yorkshire coast, with the first phase of the project generating renewable energy for the first time in October 2023.

The first two phases: Dogger Bank A and B require phases of onshore construction in the East Riding of Yorkshire. This work includes construction compounds, cable routes, substations, and off-shore converter platforms (places where offshore wind energy is integrated into the National Grid).

In the first phase of work, a geophysical survey was carried out and this established the likelihood of archaeological remains existing in certain areas. In total, 22 archaeological sites were identified in areas where construction work would have led to disturbance, and these sites were excavated in advance of construction work.

A Line Through the Landscape

The project spans the region of Holderness, between the urban centres of Bridlington to the north and Kingston upon Hull to the south. It is a landscape of gently undulating farmland dotted with small villages, following the shallow valley of the River Hull. The region extends southeast into the North Sea and is separated from the rest of the mainland by the Humber Estuary. The archaeological works included geophysical survey, trial trenching, and excavations across the area, revealing several phases of archaeological activity.

The earliest evidence comes from flint tools thought to date to the Mesolithic period (9000 – 4000 BC). Linear field systems and enclosures associated with prehistoric and historic cultivation were found throughout the area, testifying to the region’s long-lived agricultural heritage. At some sites, these were accompanied by other features, such as pits, postholes, and ring-ditches, revealing evidence of roundhouses and other structures. The artefacts associated with these sites indicate settlement in the Iron Age (800 BC – AD 43), Romano-British (AD 43 – 410), and Anglo-Saxon (AD 600 – 1100) periods.

Explore the excavated sites on the map below!

Click and drag to move the map or use the controls to zoom in and out. Click a point of interest or image to start scrolling through the guided tour.

explore the 3D models of the artefacts⚬

explore the 3D models of the artefacts⚬

explore the 3D models of the artefacts⚬

explore the 3D models of the artefacts⚬

explore the 3D models of the artefacts⚬

Neolithic kite-shaped arrowhead

This flint arrowhead is a kite-shaped form typical of the Early to Middle Neolithic (3,700 – 2,900 BC). It has been carefully flaked and retouched along the edges to create the distinct triangular shape and would have been secured to the wooden arrow shaft using natural glues. Sets of such arrows would have been kept in a quiver for use with a longbow, probably for hunting wild animals.

Flint was a valuable prehistoric resource, prized for the way it could be shaped or knapped speedily into a variety of tools and weapons with sharp edges. The raw material occurs as nodules within limestone or chalk that can be mined or collected along riverbanks and beaches. It was regularly traded over long distances and can help us to understand settlement and migration patterns as well as trade routes and flint working areas.

Iron Age / Anglo-Saxon glass bead

This yellow glass bead is of a colour that was extremely popular in Iron Age Britain from the mid-3rd century BC onwards. Its popularity declined during the Roman period but saw a resurgence in the later Anglo-Saxon period (6th century AD). This bead could have been worn by a man or woman, possibly strung as part of a necklace or bracelet, tied into hair, or attached to clothing or objects.

In the past, molten glass was shaped into many useful or decorative objects, from bottles and containers, to window, dishes and drinking glasses, jewellery, art, and more. This spherical bead would have been made by winding a thread of molten glass around a metal rod or an iron tool called a mandrel. Different compounds or chemicals were added to the glass to create a range of colours and effects.

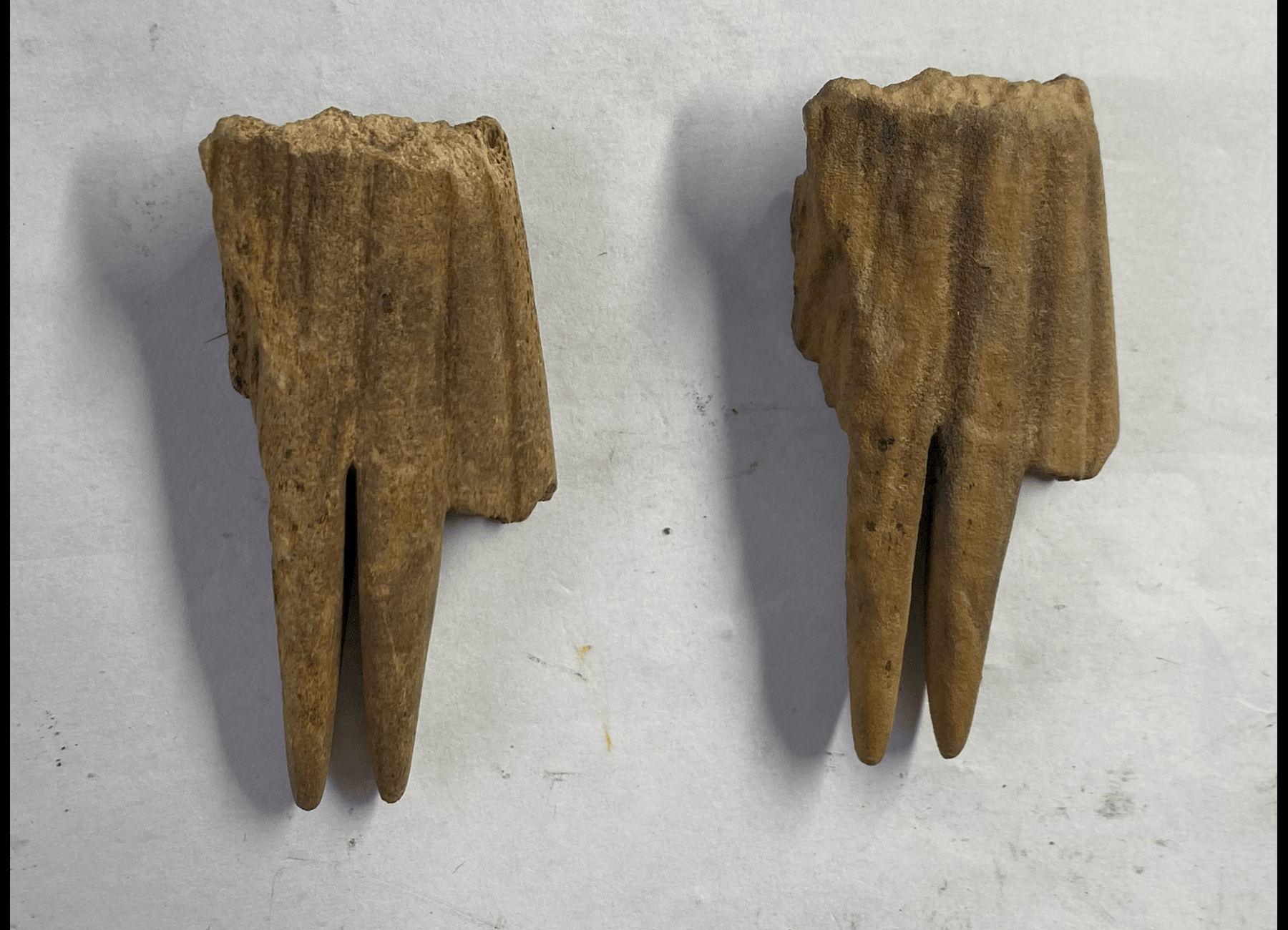

Long-handled bone comb

This long-handled comb fragment is made from red deer antler or mammal bone and is a characteristic artefact type from Iron Age sites (800 BC – AD 100). Only two of its teeth survive, but there would have originally been a row of teeth with a long handle. Such tools are associated with textile production and weaving, where they may have been used for combing wool, braiding, or preparing fibres for fabric production.

Bone and antler were favoured materials for creating objects due to their versatility and the ease with which they could be shaped, leading to the epithet ‘the plastic of prehistory’. Bone was a readily available by-product of animal butchery, alongside meat, wool, fur, skins, and sinews. A variety of techniques and tools were used to create objects, including flint borers and blades, and metal saws, drills, and chisels.

Iron Age lugged vessel

This large pottery sherd comes from a lugged bowl typical of the Pre-Roman Iron Age and Romano-British period (400 BC – AD 400). The vessel has a robust loop protruding from its rounded body, with the thickness of the loop suggesting a functional rather than decorative purpose. These lugs would have been useful as handles or in suspending the vessel from a rope during use, transit, or storage.

Ceramic vessels have been widely used throughout history and prehistory for a variety of functions including cooking, storage and serving, but it is the shape and style of the vessels that allow archaeologists to date them to a specific time period or function. Pottery often only survives as small fragments, making larger sherds such as this one so important and informative for understanding the past.

Iron Age funnel-necked vessel

This pottery fragment forms the rim, neck, and partial body of a funnel-necked vessel typical of the Pre-Roman Iron Age and Romano-British period (400 BC – AD 400). The fragment is unadorned, suggesting a functional rather than decorative use, but the surface of the pot appears to have been burnished or polished, which would have created a fine glossy finish, mimicking the appearance of buffed leather.

There is sooting on the surfaces of the vessel from exposure to fire smoke, indicating a likely function related to cooking. This is further supported by the presence of residues on the pottery that may be the remains of the food that was once being prepared. Future analysis of these residues can provide insights into the diets and cooking practices of past peoples.

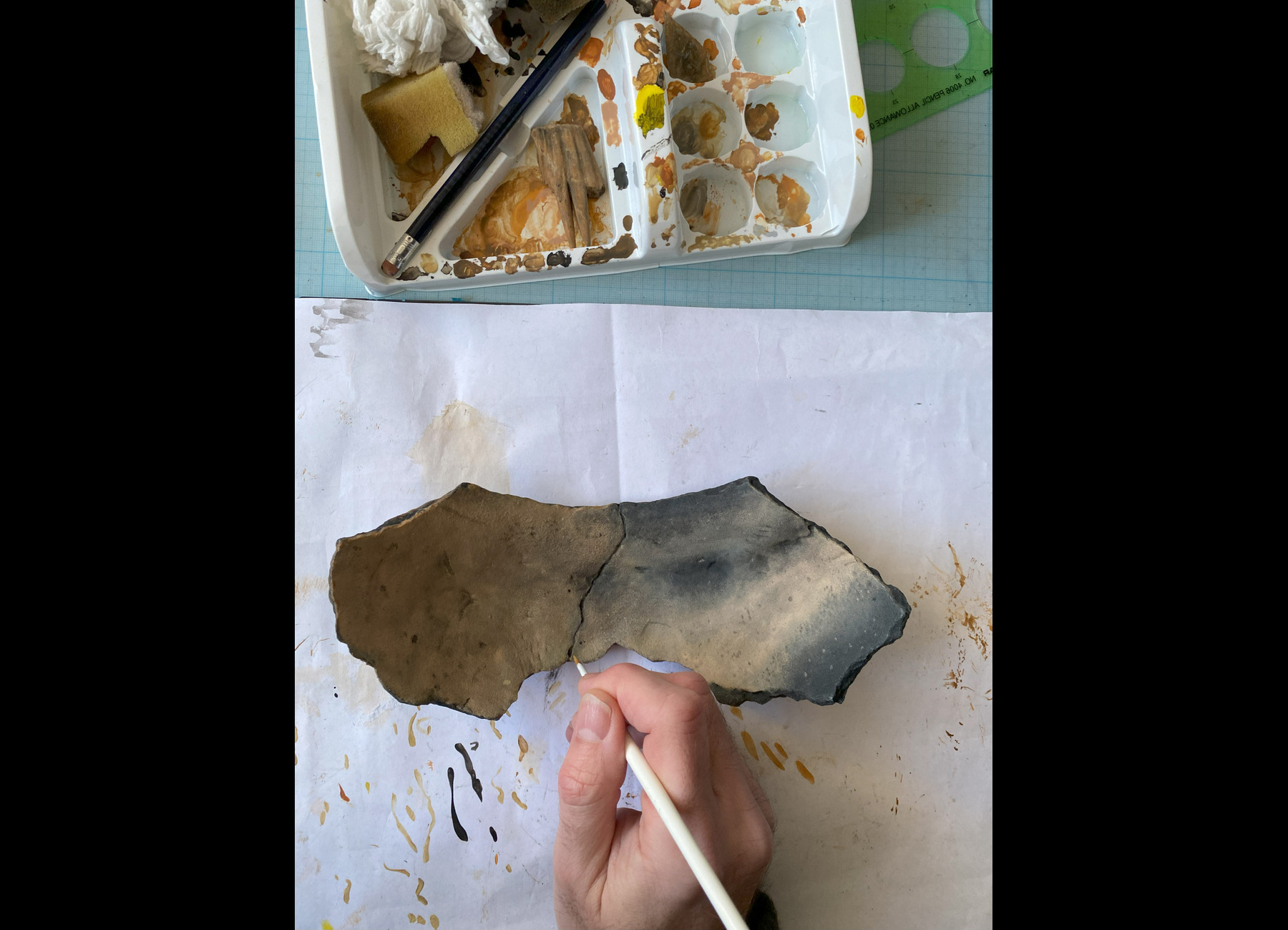

The 3D models above were created using a technique known as photogrammetry. This process involves taking lots of overlapping photographs of the objects from different angles. The photographs are then combined using specialised software to create the digital models.

The 3D models from the Dogger Bank project have been used to create replicas of these incredible artefacts to be used alongside an educational resource. They were created through a process of 3D printing, followed by hand painting of the artefacts. Take a look at some of the images below to see what the models looked like before and after painting.

Future Research

Together, the excavation sites from the Dogger Bank project provide a huge amount of information. Assemblages of ceramics, lithics, animal bone, macroplants, charcoal, and other artefacts and ecofacts have been collected from the excavations and hold great potential to further our understanding of the individual sites and the wider Iron Age and Roman settings they represent. Study of the excavated material is ongoing, with specialist analyses being carried out on the various artefact types and the recovered environmental material.

Excavating a pot on site

This future research aims to investigate several key topics, such as:

What was the nature and function of the excavated sites?

What can the artefacts tell us about activities taking place on the sites?

What was the chronology and longevity of the sites?

How do the sites compare to others in the region or further afield?