Excavations at New Street Gasworks in Canongate, Edinburgh, uncovered one of the earliest and most significant gasworks in Britain. A complex array of buildings and industrial technology survived, shedding light on the evolution of the gasworks and its huge impact on society as it brought gas lighting to the people of Edinburgh.

AOC Archaeology undertook the excavations between 2006 and 2008, as advised by the City of Edinburgh Council Archaeology Service (CECAS). The post-excavation programme was funded by New Waverley Advisors Ltd.

Harnessing the ‘Spirit of Coals’

In 1684, Rev John Clayton of Wigan ignited gas collected from heated coals and named it ‘Spirit of Coals’. He was one of several people in the 17th century credited with the discovery of gas as a fuel. During the 18th century, gas was adopted for lighting in various private settings across Britain, but by the early 19th century, the industry expanded to large-scale public supply, heralding major social changes across the country.

The world’s first Municipal gasworks were established in Westminster in 1813 by the Gas Light and Coke Company. Only a few years later, Scotland’s first gasworks were set up in Edinburgh and Glasgow, with the longer winter nights fuelling a higher demand for gas in the north than in many English towns. The New Street Gasworks, established in Canongate in 1818, was one of the earliest in Britain and stood at the fore of many technological advancements.

Drawing horizontal retorts, South Metropolitan Gasworks, London, c late 19th century

A History of Canongate

Canongate forms the street leading west from Holyrood Abbey and the Palace of Holyroodhouse towards Edinburgh Castle. The area was bestowed burgh status around 1128 during the reign of David I and was a favoured route for royalty into the city. Many wealthy residents lived along the street, attracted by its proximity to Parliament and the Royal Palace.

During the medieval period, the street would have been lined with burgage plots, narrow strips of land with a building at the street front acting as a dwelling, booth, or brewhouse. Behind the buildings, the backlands formed gardens, semi-agricultural spaces, and workshops. Many traditional traders and craftspeople occupied the area, including masons, tailors, shoemakers, weavers, hatters, stablers, coachmakers, grocers, bakers, vintners, and brewers.

The status of Canongate diminished after the Act of Union in 1707 moved the Royal seat of power away from Edinburgh and dissolved the Scottish Parliament. The wealthy residents gradually left the area in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, leaving only the poorer folk behind, many of whom lived in one-room dwellings with their whole families. As the population increased, several new streets, including New Street, were built into the backlands, facilitating the construction of new industrial sites, such as the Gasworks, Canongate Iron Foundry, and the various Canongate breweries.

Map images can be viewed in full at the National Library of Scotland online map viewer.

Lighting Up Society

Prior to the use of public gas lighting, Edinburgh’s streets would have been lit by candle or oil lamps, most of which would have been extinguished around 9 or 10 o’clock. This made the streets dangerous and dirty places at night, as people disposed of waste out of windows or unsavoury characters prowled the darkened lanes and closes. The introduction of gas lighting to Edinburgh made the city a safer and more sociable place, removing the limitations that the hours of darkness placed on activities. It was safer to walk the streets at night, people could work longer hours, and Edinburgh’s industrial revolution could flourish.

The New Street Gasworks chimney seen through the Edinburgh smog in the late 19th century © Courtesy of HES (Scottish Gas Collection).

The New Street coal shed in operation © Courtesy of HES (Scottish Gas Collection).

The Dark Side of Gas

Despite the social benefits of gas lighting, those who lived and worked near the gasworks felt the negative effects of the industry in full force. Local residents complained of polluted water and noxious fumes in the air. Those working in the gasworks faced day to day physically demanding labour within the heat of furnaces and noxious gases. The corrosive gases produced during the processes were strong enough to degrade iron and steel, but while efforts were made to improve the durability of the metal fittings, less concern was given to the welfare of employees.

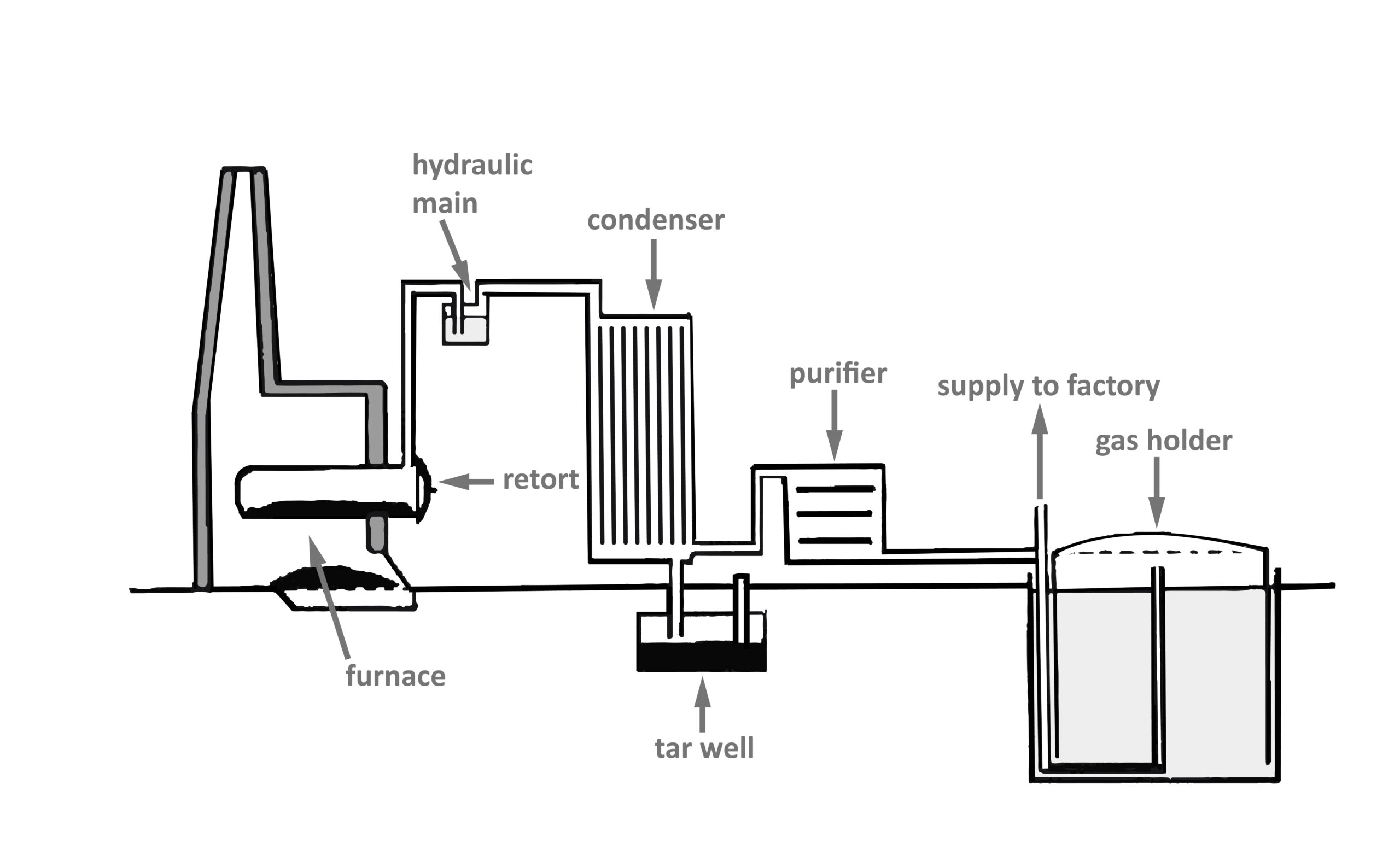

From Coal to Light

Gas was produced by heating coal in a closed tubular vessel, known as a retort. The heated coal gave off a mixture of hydrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide, which could be stored in gasholders for later use. The stored gas was then delivered to houses, streets, and other establishments through buried pipes, where it could be ignited to produce light.

The Furnace provided the heat source for the retorts, often using residual coke as fuel.

The Furnace provided the heat source for the retorts, often using residual coke as fuel.  The Retorts were airtight cylinders that held the coal. Because of the sealed environment, the heat forced the gases out of the coal, leaving behind a residue called coke.

The Retorts were airtight cylinders that held the coal. Because of the sealed environment, the heat forced the gases out of the coal, leaving behind a residue called coke.  The Condenser cooled the gas, allowing volatile inclusions, such as tar, to be siphoned off as they cooled into liquids. These collected in the Tar Well.

The Condenser cooled the gas, allowing volatile inclusions, such as tar, to be siphoned off as they cooled into liquids. These collected in the Tar Well. New Street Gasworks

New Street Gasworks was one of the earliest in Britain, established in 1818 following an Act of Parliament. It supplied Edinburgh with fuel for gaslight, and later for cooking and heating, from 1818 to its closure around 1906. Its location on Canongate made it the centre of Edinburgh’s gas industry, and its expansion throughout the 19th century eventually saw it supplying half a million people. The gasworks chimney was a prominent landmark on the Edinburgh skyline for many years, even after the gasworks closed.

Excavation of the site revealed four major phases of activity: the pre-gasworks backland gardens; the early gasworks (1818 – 1845); mid-19th century expansion (1845 – 1875); and the final stages of the gasworks (1875 – 1906). The gasworks saw continual modification and innovation as the site expanded to full capacity and techniques were constantly refined to combat the negative effects of pollution. Many of the foundations and features uncovered can be linked to those depicted on historic mapping throughout the century.

Explore the excavation highlights below, and if you want to learn more, check out our publication for full details. The primary archives are to be deposited with the National Record of the Historic Environment and subject to allocation by the Scottish Treasure Trove Unit and the KLTR the finds are expected to form part of the City of Edinburgh Councils Archaeology Collections.

Use the map to explore the excavation: click and drag to move the map or use the zoom controls to move in and out. Click on a marker for more information or click an image on the left to start a guided tour.

explore the 3D model⚬

explore the 3D model⚬

explore the 3D model⚬

explore the 3D model⚬

explore the 3D model⚬

Artefacts

Large quantities of artefacts were found during the excavations at New Street Gasworks, including metal, wood and stone fittings, fixtures and tools; painted architectural mouldings; a refractory ceramic retort; leather shoes; worked bone and metal dress accessories; glass bottles; tableware and pottery. Hover over the images below to learn more about the main types of artefacts found.

Scotland’s Earliest Pipe

One of the tobacco-smoking pipes found during the excavation is the earliest Scottish-made example to have been found on a site in Scotland. It is datable to around 1610-1620 and bears the castle basal stamp of William Banks, who was a recorded pipemaker in Edinburgh in the early 17th century, when he held a monopoly over the trade. Other 17th and 18th century pipes from other Edinburgh pipemakers, as well as Dutch and English style pipes, were also found on the site.

The Intact Fireclay Retort

The survival of an intact fireclay retort at New Street is unusual as retorts were usually broken up and buried when they could no longer be used. The retort is a D-shaped cylinder measuring 1.57m long, with the name of its manufacturer, Glenboig, stamped at the top.

Encaustic Tile

This decorative fragment of an encaustic tile probably came from a floor surface in one of the gasworks buildings. It gives a glimpse into what the public areas of the gasworks might have looked like.

Gasworks Shovel

This degraded shovel blade is a tangible insight into the everyday tasks carried out at the gasworks. It was probably used to shovel coal from wooden carts onto a massive pile kept in the coal sheds.

Porcelain Figure

A bisque porcelain figure of a Russian boy was found in the excavations, wearing a fur hat, green baggy trousers, yellow scarf and brown clogs.

Medieval Ceramics

Sherds from late 12th/13th century ceramic vessels were found on the site, relating to the activities that happened before the gasworks were built.

Retort Inspection Box

This iron box was built into the brickwork structure of the furnace. It had a sliding door attached to a chain, allowing the panel to be pulled open for workers to assess the furnace and temperature of the retorts.

Glass Bottles

Many mid-19th to early-20th century bottles were recovered from the site, most from the period of the gasworks expansion in the late-19th century. They included wine, beer and spirit bottles, aerated water bottles, medicine bottles, and food storage containers.

Brass Oil Lamp

This fitting came from a brass oil lamp, which would have held a glass cover to protect the flame. The fitting has a threaded base, which would have screwed into an oil reserve with a thumbwheel for controlling the flame size.

Shoes

Remains of 15 shoes were found during the excavations. The soles were riveted to the uppers, a style associated with cheap, mass-produced footwear from the late 19th century. The range of sizes indicate the wearers were both children and adults, with at least one woman’s shoe present. Although cheaply made, the shoes were sturdy and attention to detail was not sacrificed.