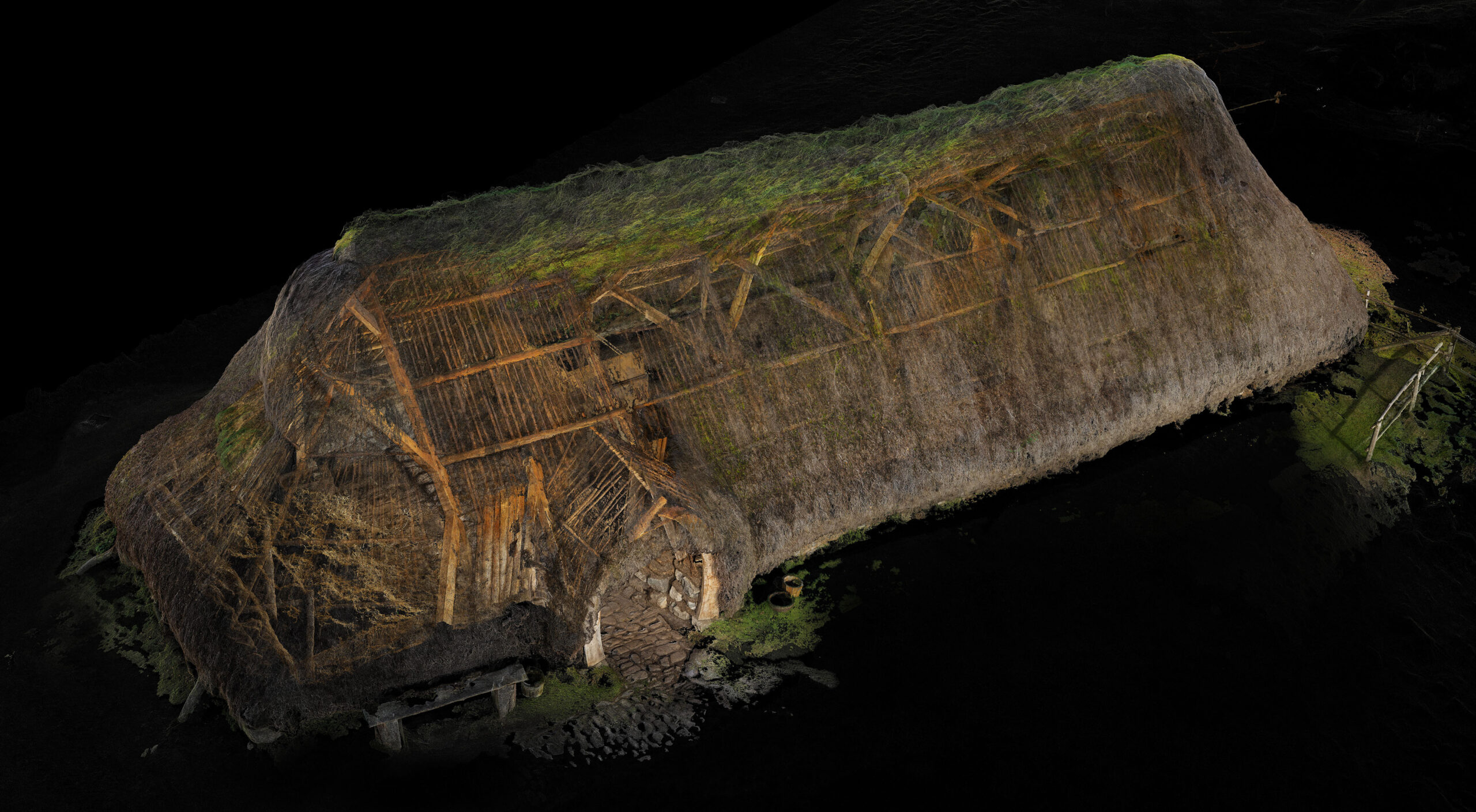

The Tacksman’s House at High Life Highland’s Highland Folk Museum is the largest of the thatched buildings at the recreated 1700s township near Newtonmore.

New 3D modelling of the building, undertaken by AOC Archaeology in 2021 as part of a wider digital tour of the open-air museum, provides a new dimension for people to explore the past.

The Tacksman’s House – The Centre of the Community

The Tacksman’s House is the largest domestic structure within the recreated township of Baile Gean (meaning ‘Township of Goodwill’ in Gaelic). The reconstruction was based on a combination of physical archaeological evidence, documentary research, and practical experimentation. The house and other buildings in Baile Gean mirror their real-life counterparts in the nearby, abandoned township of Easter Raitts, which would have been one of the main settlements in the Badenoch area through the Post-medieval period up to the 1790s when the planned town of Kingussie was established.

The building is an excellent example of Scottish vernacular architecture, which made use of locally available, natural materials, such as stone, timber, turf, and heather for construction.

The Tacksman was the principal tenant of the township, who held the lease for the land and sub-let it to the other tenants. His role involved negotiating, collecting, and paying the rent, as well as being the liaison between the township and their landlord, the local laird or chief. Tacksmen formed a middle class in Highland society, and they had an important community status, in some cases being a relative of the landlord. Generally, they made their living through a mixture of farming and the profits made through collecting the rent. The larger size of his house was likely due to his greater wealth, and it is likely he would have owned higher status furniture and objects.

Construction – Crucks, Couples, and Cabers

The Tacksman’s House is a cruck-framed structure, typical of Medieval and Post-medieval settlement throughout Scotland. The main characteristic of this type of building was the cruck frame couples, a series of arched timbers which carried the weight of the roof directly to the ground and allowed the walls to be made of lighter materials. The cruck couples could be made from a pair of arched timbers or several peg-jointed pieces. Horizontal timbers called collars or tie-beams were used to strengthen the frame.

The house was constructed with a lower foundation of stones, which supported the main turf walls. Timber purlins (horizontal beams) and cabers (vertical beams) formed the frame of the roof, on top of which was laid a layer of turf, then thatch. The thatch was usually made from local vegetation, such as heather, broom, bracken, or reeds, though heather was the most common. The Tacksman’s House at the Highland Folk museum has a roof thatched with broom and heather, with the ridge sealed by a layer of turf. The roof extends almost to the ground, protecting the turf walls from the elements. Every five to ten years, an extra layer of thatch is added.

Inside the House

The interior of the Tacksman’s House, although formed by one single space, was split into three areas. At one end was the byre, and at the other end was the Guid Room, with a central living space between the two. The building has one entrance and no windows. The backdoor seen in the reconstruction is not authentic but included to comply with current building regulations.

The byre housed the native, small black cattle (kyloe), particularly in the winter months. The ground here was cobbled to limit the effects of churning hooves, and the central channel acted as a drain to take urine and wastewater out underneath the back wall. Cattle were an important part of the local economy, providing dairy produce for everyday living. Income also came from rearing calves, which were later sent by drove roads to the southern cattle fairs.

The central room formed the main living space for the Tacksman and his family. There was a central open hearth, where a small peat fire would have been kept burning at all times. As the building had no chimneys, the smoke rose up and filtered out through the roof, both helping to keep it dry and free from insects. The fire was central to Highland life, holding an almost mystical significance, and would have been the focus for community and family gatherings.

The Guid Room was the finest and most private part of the house. It would have been kept for use by guests and for special occasions, such as births, marriages, and deaths. Box beds were where the family and guests slept and were also used to create partitions between the rooms.

3D Recording

The 3D model of the Tacksman’s House was created by combing two methods of 3D recording: photogrammetry, and laser scanning.

Hundreds of photographs were taken of the building at different but overlapping angles and scales. Specialist software was then used to stitch the photographs and scans together and add the colours and textures.

Models were also created of some artefacts from the Highland Folk Museum collections, including a tin lantern, and two traditional bonnets.

Tin Lantern

This tin lantern is from Skye and dates from the 19th century. Tin-smithing was one of the crafts which Highland Travellers were particularly well known for, and the making of lanterns was a Traveller speciality.

The lanterns were pierced with varied patterns made from lines, dots, and crosses, which let some air in and allowed light to spread out. They were also known as stable lanterns, as they were often used as lighting in the outbuildings. The round window in the hinged door is made from the base of a stemmed drinking glass.

Travelling people have been part of Highland culture for centuries. In addition to carrying out seasonal jobs such as helping on farms at harvest times, Travellers would also make items to sell or trade. They were known to be skilled silversmiths, tinsmiths, horn-workers, and basket-makers. Lanterns like this were one of the types of objects that Travellers would make on the road. Before electricity was commonplace in the Highlands, lanterns and candles were an essential part of life.

Scottish Bonnet

This traditional Scottish cotton bonnet dates from the 19th century and is known as a mutch. It was commonly worn by married and older women up until the early 1900s in some areas. The bonnet would have kept a woman’s hair clean and tidy as she went about her jobs on the croft and would have also afforded her some protection from the elements. For some, bonnets may have been worn for religious reasons or as a means of modesty.

Mutches varied from very fines ones with insets of lace to simple ones for everyday use or nightcaps. Goffering irons were used to press the immaculate frills, and special boxes were used to carry a freshly laundered mutch to church.

Tam o’Shanter

This Scottish woollen cap with its red toorie (pompom) dates from the mid to late 1800s and is known as a Tam o’ Shanter. It was traditionally worn by men and named after the central character in the Robert Burns poem of the same name.

Tam o’ Shanter is an epic poem written in a mixture of Scots and English in 1790. The poem is set in Ayr and follows the tale of Tam o’ Shanter, a local farmer who rides home in a storm after getting drunk at the pub. On his way home, Tam sees a gathering of witches and warlocks at the local haunted church. After disturbing their revelries, Tam and his horse Meg are pursued to the River Doon where they manage to escape but only after Meg loses her tail. In the poem Tam is described as ‘holding fast his gude blue bonnet’.

Woollen bonnets were knitted in one large piece, often twice the size of the finished article, then shrunk down by a felting process, which also made the hats almost waterproof. According to James Logan, writing in his 1876 book “The Scottish Gael”, the inhabitants of Badenoch, Strathspey, and Strathdon wore their bonnets cocked.

Earlier forms of these caps were more commonly called Blue Bonnets as most were coloured with natural dyes such as woad. They were worn across the Lowlands from the 16th century onwards but were adopted later in the Highlands. The Blue Bonnet has long been associated with romanticised views of Scottish culture, but it was also adopted into the symbolism of major political movements, such as the Covenanters and the Jacobites. Later, various forms of the Blue Bonnet and Tam o’ Shanter were used in military regiments.